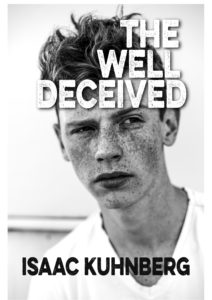

My Five Favourite Things About The Well Deceived by Isaac Kuhnberg

My Five Favourite Things About The Well Deceived by Isaac Kuhnberg

Hi all! Today is my stop on the The Well Deceived blog tour and I have the lovely Isaac Kuhnberg on the blog today talking about his favourite things about his book!

My Five Favourite Things About The Well Deceived

Narrative strategy.

William Riddle, the protagonist of The Well Deceived, is a young man with a fair degree of intelligence and insight, who is at the same time wholly ignorant of the most basic truth about the society he lives in. Making him the narrator of his own story was a strategy I adopted instinctively, before I had written a line. It turned out to be a crucial decision, allowing me to position myself squarely behind his eyes, and see the action as he sees it himself, through a flawed lens.

Once I had worked out the basic facts of William’s situation, I set him in motion, and waited to hear what he would say. Happily, he said a great deal, with very little direction from me. The unconscious had taken over – fed as always by memory, reading, research, current events – and I could sit back and allow the novel to write itself. This does not always happen, but when it does it makes the generally agonizing process of writing a great deal easier. If you are lucky, it also invests a character with a certain authenticity: they start thinking for themselves, and acting and reacting on their own account; and sometimes their thoughts and actions come as a surprise – even a shock. Writing, as Graham Greene once said, is a form of therapy: it allows you to express a great deal you did not know what you felt. That does not means, of course, that what you write in that state will be any good.

The Malcaster Stories

Whenever I needed a break from William’s introspection, I amused myself by composing passages from the stories written by William Riddle and Paul Purkis at Bune School, all of which are set in an imaginary town called Malcaster, which is a grotesque version of the town where Bune School is situated. The stories are on one level parodies of popular Edwardian thrillers – they feature two detectives not unlike Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson — but the overriding tone is appropriately juvenile. Noir surprisingly the Bune headmaster condemns them as the product of malice and schoolboy smut. Nonetheless the boys obviously found them great fun to write, and so did I.

Parallels

Since William’s country, Anglia, exists in an alternative universe, it contains many parallels with our own society: places and customs and institutions and painters and writers. One example I hope the reader will enjoy is the first century dramatist Andrew Wagstaffe, author of Tarquin, Prince of Antibia, and something of a local hero in Arden, the northern city where William and his lover Mark visit during an election campaign. Again, lots of fun to write.

Another point of view

Another parallel character I enjoyed writing about is the painter Daniel Higgins, who offers William a refuge when he is on the run and has shot himself in the foot. This character is actually modelled on two English painters: no doubt most readers will guess who I had in mind. A later chapter features a review by an art critic called Pearse de Blaby, who writes glowingly about a painting by Higgins entitled ‘Young Man with Bandaged Foot.’ The model’s face, he writes, “is suffused with a species of self-regard more unbecoming than any deformity.” As always, there are as many ways of seeing an event as there are persons to see it.

A puzzle within a puzzle within a puzzle

The structure of the book developed as I wrote it, drawing on the same instincts which shaped the character and role of William Riddle. The imaginary town which William calls Malcaster is a distorted reflection of Anglia, which is in turn a distorted reflection of England in the 1950s. The immediate reality is contained within a larger one, which is contained within a larger one still: each being a mystery that only poses further questions, all of which are ultimately unanswerable. All experience is necessarily subjective; every model of reality is untrustworthy in some respect or other. When Anne Frank’s father was asked if the restored secret annexe should be furnished as it was when the family was hiding from the Nazis, he said he wanted it left empty, defined by his feeling of loss. The only reality we truly comprehend is the reality of our own emotions.

About the book

A thought-provoking mystery in turns comic and disturbing, set in a country that resembles England in the 1950s, with one crucial difference. No women.

A thought-provoking mystery in turns comic and disturbing, set in a country that resembles England in the 1950s, with one crucial difference. No women.

William Riddle is a scholar at Bune, the ancient public school where the sons of Anglia’s first families are prepared for a leading role in society. His first few weeks are a miserable round of bullying and abuse, until he makes a friend: Paul Purkis, son of a government minister. Together they create a grotesque private world, known as Malcaster, populated by criminals and deviants, as an outlet for their contempt for the school and its staff.

Overnight William’s world collapses. He is called into the headmaster’s office and told that his scientist father has committed an unspecified act of treason. William is hauled off to a detention centre to be interrogated. Escaping, he finds refuge in the louche sub-culture of the capital city, and comes to learn that everything he has ever been taught is a complete fabrication.